The Birth of a Union: Theatricality, Sympathy, and Anti-Slavery in the Coming of America’s Civil War, 1830–1860

Michael Amico

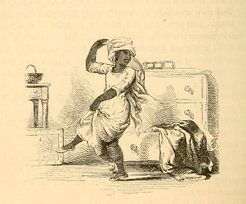

How blackface minstrelsy helped generate anti-slavery sentiment in mid-19th-century America: The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin has long been accepted as among the most effective means by which northerners came to feel differently about slavery and adopt anti-slavery positions. The effect was centrally achieved through the theater, where an estimated 50 times more people encountered the material than read Stowe’s novel. Moral reformers of the time, and most scholars of today, believe that the white male working-class audience came around to anti-slavery by identification with the suffering and resisting slaves depicted in the play. But to pin the process of the audience’s growing sympathy to only the content of the show does not adequately consider how the audience experienced and enjoyed it as blackface performance.

This project takes a renewed look into how a uniting spirit took shape in mid-19th-century America and inspired people of the northern states to fight a war against the slaveholding south. While it is customary to consider blackface performance as morally offensive and so unrelated to the otherwise morally uplifting content of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, this presentist position misses how interracial relations were worked through in a particular style of performance and thus obscures the emotional makeup of what historians have had trouble accounting for in purely political, economic, or moral terms.

The focus on blackface and Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a central component of my broader research into how northern America, in the lead-up to the Civil War, came together as a “union” for the first time. How did this happen? What comprised the sense of unity? The first major piece of this research concerned how the highly sexualized friendship of two northern soldiers challenges our understanding of the emotionality of the larger social union. Thinking further about what comprises this feeling on the social level, this current project also finds the question of sex and friendship to be integral to the bonds white men felt for black men, particularly as they were explored through the grotesque song and dance of blackface minstrelsy.

The sources for this project include texts and music of songs, scripts of performances, the design of theaters and their neighborhoods, reviews and advertisements of plays, and personal testimonies of performances as preserved in letters, diaries, and newspapers. The method consists of identifying the emotions expressed in and through these sources and inquiring into their animating objects, both material and fantastical (e.g. joy around “what”? Anger over “what”?). This method has revealed how the emotions in and around Uncle Tom’s Cabin were less about slavery per se than the constraints on and allowances for an arousing and thrilling sense of play in one’s day-to-day life. What also comes into view is how the larger, more amorphous space of fellow feeling was not curtailed by its many racist expressions.