The Heuristic Mind

How to Tap Into the Information Trove That Is One’s Personal Environment

Heuristics in Decision Making With External Information Search

A Theory of Ecological Structure: How Risks and Rewards Get Coupled in the Environment

The Hazards of Complexity in Modeling Cognition: Parameter Interdependencies

Making good decisions is not a simple feat. Ubiquitous conditions, such as bounds on information, time, and computational resources, can render the reckoning with risk and uncertainty a challenge. We argue that people respond to this challenge by harnessing simple but often highly efficient decision-making rules—heuristics. Our aim is to identify and describe these heuristics, to understand how they exploit statistical properties of the environment and what can be learned about these properties, and how people adapt their use of different heuristics to the environment in question.

How to Tap Into the Information Trove That Is One’s Personal Environment

A person’s social network constitutes a rich sampling space for making inferences about the distribution of social statistics, including other people’s preferences, opinions, or behaviors. How do people search this personal sampling space and use it when making such inferences about social statistics?

We (Schulze et al., 2021) developed the social-circle model to explain how people make inferences about social statistics by using their personal environment as an information search space. The model assumes that a person's internal representation of their social network is structured as distinct social circles of self, family, friends, and acquaintances. Our model outperformed both simpler and more complex competitor models and revealed interesting differences in the process of social sampling between adults and children. For instance, children weighted their “self” circle more heavily than adults did. By understanding how people tap into the information trove that is their proximate social environment, we hope to better understand how people learn, without instruction, from their social world and how they rely on it to infer important social statistics.

Figure 1. Illustration of the task screen used in the inference task (Panel a) and retrieval task (Panel b) in Schulze et al. (2021; Study 2). In the retrieval task, each participant indicated how many members of their social network had experienced the relevant events (e.g., whether they had spent a vacation in Italy) and to which social circle they belonged. These responses were used to derive the predictions of the social-circle model for participants’ responses in the inference task. Panels c and d show the distributions of the medians of each individual’s posterior distribution of social-circle model (SCM) parameter estimates in Study 2 of Schulze et al. (2021) for the adults and children, respectively. The lines link the estimated circle-weight parameters of each participant.

Figure: American Psychological Association

Adapted from Schulze et al. (2021)

Key Reference

Heuristics in Decision Making With External Information Search

Many assume that in decision making based on information that is overtly presented in the environment—so-called decisions from givens—heuristics play only a modest role. In decisions from givens, the cost of information acquisition is relatively low, thus precluding any need for simplification.

However, we (Pachur, 2022) showed that the costs of gathering and integrating information in visual search can become quite high when the amount of information exceeds a certain threshold (around four units). In light of these mental costs, people may rely on heuristics even in decisions from givens because of one of their key strengths: the reduction of mental costs. To test this hypothesis, participants judged which of two diamonds was more valuable, with each diamond described in terms of either four or eight attributes. A novel Bayesian classification method that considers both a person’s decision and their response-time patterns found that the proportion of participants using a simple heuristic was higher when eight attributes were presented, compared to four. Moreover, those participants who used a more complex compensatory strategy in the eight-attribute condition displayed high error rates, demonstrating the costs of search and integration (Figure 2b). Our findings highlight the role that heuristics play in decision making from givens.

Figure 2. Panel a: The task screen of the different experimental conditions in Pachur (2022). Panel b: The estimated strategy execution error in the different conditions, separately for participants classified as using a compensatory or a noncompensatory strategy. Manipulating the type of coding of the attributes (uniform versus varied) had only a minor effect on strategy use.

Figure: Elsevier

Adapted from Pachur (2022)

Key Reference

A Theory of Ecological Structure: How Risks and Rewards Get Coupled in the Environment

Many choice environments reveal a tight coupling of risks and rewards, or probabilities and payoffs. Specifically, they are coupled in such a way that high payoffs occur only with low probabilities. An adaptive mind can exploit this association by, for instance, using a potential reward size to infer the probability of obtaining it. This would offer people a simple way to reduce uncertainty. However, a mind can only adapt to and exploit such an environmental structure if it is frequent and recurrent.

We (Pleskac et al., 2021) developed the competitive risk–reward ecology theory (CET) that explains why the ecology of competition can make the association of high rewards with low probabilities ubiquitous. CET is based on the ideal free distribution principle. It states that competitors in a resource-rich environment will spread themselves out proportionally to, roughly speaking, the size of the resource patches. This principle implies that high rewards are associated with low probabilities because of others competing for the high rewards. Importantly, CET permits one to derive predictions about the boundaries of this relationship, such as how it degrades when the system is out of equilibrium. It also explains how various ecological factors can impact the relationship, for example, how computational and resource limitations lead to a shallower risk–reward relationship and how smaller rewards are associated with a larger range of probabilities.

Reanalyzing existing data and on the basis of new experiments, we found that people’s mental representations and beliefs reveal the patterns that CET predicts. We further showed that people’s estimates of probability changed with a variety of changing ecological conditions, as predicted by CET. Taken together, these results and insights highlight the necessity of not just describing those environmental structures that are relevant for human cognition but also developing theories for classes of environments. Only then can we predict when and how these environments support or hamper the mind’s inferential machinery.

Key Reference

The Hazards of Complexity in Modeling Cognition: Parameter Interdependencies

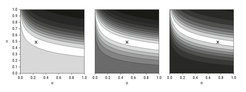

A key insight from ARC’s research is that human decision-makers often rely on simple tools to address the challenges of a complex and uncertain world. More complex strategies, by contrast, can hamper good decision making. Trying to better understand the strengths and weaknesses of complex models commonly used in behavioral decision science, we (Krefeld-Schwalb et al., 2022) explored how fragile these complex models are. Specifically, we assumed that many adjustable parameters can compromise the usefulness of complex models of cognition. Models of recall and preferential choice commonly compute a subjective value for objects. They, in turn, are entered into a choice rule that determines the model's prediction of observable behavior. This rule is typically equipped with a free parameter that characterizes how deterministic versus noisy a behavior is. Our formal analyses and computer simulations of several prominent models of cognition (the general context model of categorization, the SIMPLE model of memory, and cumulative prospect theory for risky choice) revealed that this architecture gives rise to substantial interdependencies between the parameters involved in computing the subjective value and this noise parameter (as seen in Figure 3). These interdependencies, in turn, lead to considerable problems when recovering parameter values. Specifically, models suggest possibly distorted conclusions about the real values in human participants. We discussed and tested several approaches to simplifying the models to improve recoverability. Our analyses suggest that, as in the case of cognition itself, less complexity can be more when it comes to modeling cognition.

Figure 3. Likelihood surface showing the goodness of fit (negative log likelihood) of the model for different combinations of the value function parameter α and the noise parameter θ. Results are shown for three levels of noise in the generating model (θ = .25, .5, and .75, in the left, middle, and right panels, respectively). Darker shading indicates lower fit. The crosses indicate the parameter values that were used to generate the data.

Figure: American Psychological Association

Adapted from Krefeld-Schwalb et al. (2022)

Key Reference