The Unf inished Mind

Evolutionary Roots of Risk Preference, Reasoning, and Decision Making

Experience as a Key Factor in Shaping Statistical Intuitions Across Ontogenetic Development

Social Influence in Adolescent Risk Taking and Decision Making

People of all ages face uncertainty and risky situations throughout their lives. But what are the evolutionary and developmental origins of human decision making under uncertainty? How do children learn to manage an unpredictable world? And what role do social factors play in risk taking among adolescents? To answer these questions, we have used a variety of methods (such as behavioral and observational data and formalized computational models) to understand how our ability to make adaptive decisions in different situations develops over individual and evolutionary timescales. We have also explored possible implications of our findings for education.

Evolutionary Roots of Risk Preference, Reasoning, and Decision Making

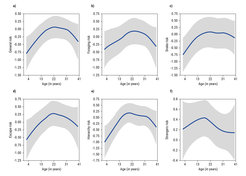

Risk preferences influence many of the decisions people make in their lives—whether to explore new areas in search of food, shelter, or mates; compete for social status; or engage in financial investments. Indeed, as a key building block in decision processes that shape individuals’ health, wealth, and well-being, an individual’s risk preference has the potential to influence the entire course of their life. Yet the evolutionary roots of human risk preference remain poorly understood. Studying chimpanzees from infancy to adulthood, we (Haux et al., 2023) used a novel multimethod approach that combined observer ratings with behavioral choice experiments to determine whether the willingness to take risks in one of humans’ closest living relatives is similar to that in humans. We found that chimpanzee and human risk preferences share key structural similarities: (a) chimpanzees’ willingness to take risks manifests as a trait-like preference that is consistent across domains and measures; (b) chimpanzees are ambiguity averse; (c) male chimpanzees are more risk-prone than females; and (d) chimpanzees’ appetite for risk shows an inverted-U-shaped relation to age that peaks during young adulthood (Figure 1). These evolutionary continuities are likely to reflect adaptations to similar dynamics in human and nonhuman primate life histories.

Figure 1. Age differences (aggregated across male and female chimpanzees) in mean levels of general and domain-specific willingness to take risks: regression splines with shaded 95% credible intervals. The domains represent major classes of risks in chimpanzees’ ecology.

Adapted from Haux et al. (2023)

Original figure licensed under CC BY 4.0

Uncertainty can arise in interactions with both social partners and nonliving objects. Previous research has shown that humans are more averse to uncertainty arising from social interactions than to uncertainty caused by interactions with objects such as gambling machines, and that this difference may be mediated by betrayal aversion. In other words, when compared to placing trust in other people, we may place too much trust in machines. Tracing the phylogenetic origins of this tendency, we (Haux et al., 2021) investigated whether chimpanzees differentiate between social and nonsocial forms of uncertainty. Chimpanzees participated in two experiments, each involving a social condition, in which the outcomes of some decisions depended on the behavior of another chimpanzee, and a nonsocial condition (i.e., playing against a machine). In both experiments, choosing the safe option resulted in immediate access to low-value food. Choosing the uncertain option could result in access to high-value food, but only if the partner (social condition) or a machine (nonsocial condition) proved trustworthy. In the first experiment, chimpanzees had no prior information on reciprocation rates (i.e., decided under uncertainty). Here chimpanzees were less likely to choose the uncertain option when they interacted with a partner than when they interacted with a machine. When they did choose the uncertain option, chimpanzees also hesitated longer in the social condition. In the second experiment, where chimpanzees had learned the statistical probabilities on reciprocation rates (i.e., decided under risk as opposed to uncertainty), they did not distinguish between social and nonsocial situations. They were generally risk averse. These results suggest that chimpanzees, like humans, are more averse to engaging in uncertain choices when the source of uncertainty is social.

Key References

Experience as a Key Factor in Shaping Statistical Intuitions Across Ontogenetic Development

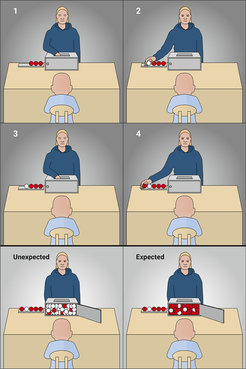

How do children and adults learn to deal with an uncertain world? The origins of the human ability to process uncertain and probabilistic information have recently been traced to infancy: Babies are already surprisingly sophisticated intuitive statisticians. But whereas infants have been found to be remarkably capable of statistical learning and inference, adults’ statistical inferences are often argued to be inconsistent with the rules of probability theory and statistics. Similarly, whereas animals appear to be strikingly risk-savvy, humans often seem “irrational” when dealing with probabilistic information. Drawing on research on the description–experience gap in risky choice, we (Schulze & Hertwig, 2021) suggested that a key factor in understanding these (and other) inconsistencies in statistical intuition research is whether probabilistic inferences are based on symbolic, abstract descriptions or on the direct experience of statistical information (see also the subsection How Experimental Methods Shape Views on Human Rationality and Competence in The Exploring Mind section). Because infants (and, similarly, animals) can neither produce nor process symbolic descriptions of the world, their statistical intuitions need to be studied in paradigms that involve experiencing probabilistic information (see Figure 2). Adults, by contrast—and this is one of the greatest cultural achievements of humankind—can communicate by means of written symbols. Consequently, since the 1970s, research on adults’ statistical thinking has almost exclusively relied on described scenarios in which all information is packaged in summary descriptions. This difference in experimental protocols, however, is consequential—our work demonstrates that it is one key to understanding several puzzling inconsistencies in statistical intuition research.

Figure 2. Illustration of an experimental paradigm used in research on infants’ statistical intuitions. The experimenter draws several colored balls (e.g., red or white) from an opaque box without looking, the contents of the box are revealed, and the infant’s looking time is recorded. If the sample drawn does not reflect the object distribution in the box (unexpected outcome, bottom left panel), infants tend to look at the contents of the box for longer than if the sample is consistent with the object distribution (expected outcome, bottom right panel).

Indeed, our research has also shown that experiencing statistical information is essential to improving adults’ and children’s ability to make decisions when dealing with uncertainty—a conclusion that has important implications for education policy. Collaborating with pedagogical researchers, we (Schulze et al., 2021) argued that the description–experience framework of statistical intuition can be harnessed to enrich formal education and, ultimately, help determine how early experience-based strategies for dealing with uncertain information can support more formal views of probability taught in school. For example, we have proposed that incorporating more experiential approaches such as experiments and case studies, alongside text analysis, into the teaching of social sciences in school may help students gain a more comprehensive understanding of complex topics.

Adapted from Schulze and Hertwig (2021)

Original figure licensed under CC BY 4.0

Key References

Social Influence in Adolescent Risk Taking and Decision Making

When observing them, one might think that adolescents are a different species altogether, typically being excessively risk taking and sensitive to peer influence. Various theories of adolescent behavior attribute this to their immature cognitive control, sensation seeking, or social motivation. At the same time, many agree that some adolescent risk-taking behavior is adaptive. Yet, what it means to be adaptive during development is largely undefined. We (Ciranka & van den Bos, 2021) argued that understanding the potential adaptivity of adolescent risk taking requires attending to adolescents’ developmental goals and the environment they interact with to achieve them. Inspired by theories that conceptualize human development as optimization, we understand adolescents as learning agents in a complex and uncertain environment to which they increasingly adapt in the course of their development. We identified three unique properties of the adolescent landscape of opportunities and social environment: (1) greater opportunities to take risks, (2) novel opportunities with uncertain outcomes, and (3) peers becoming more influential. We used agent-based modeling to illustrate how adolescent risk taking may emerge from learning about an uncertain and unpredictable environment. We showed that a typical inverted-U-shaped age trajectory in risk taking may emerge without a specific adolescent motivational drive for sensation seeking or sensitivity to social information. Notably, and aligning with our experimental work, agents used social information the most when uncertainty was high. The simulations also showed how risky exploration may be necessary for adolescents to gain long-term benefits in later developmental stages and that social learning can help reduce losses. This work thus provides an ecological perspective on risk taking in adolescents by viewing them as learning and adapting agents.

Key Reference